The Sound that will never leave you

By Glenn Patterson

For National Museums Northern Ireland

0:00

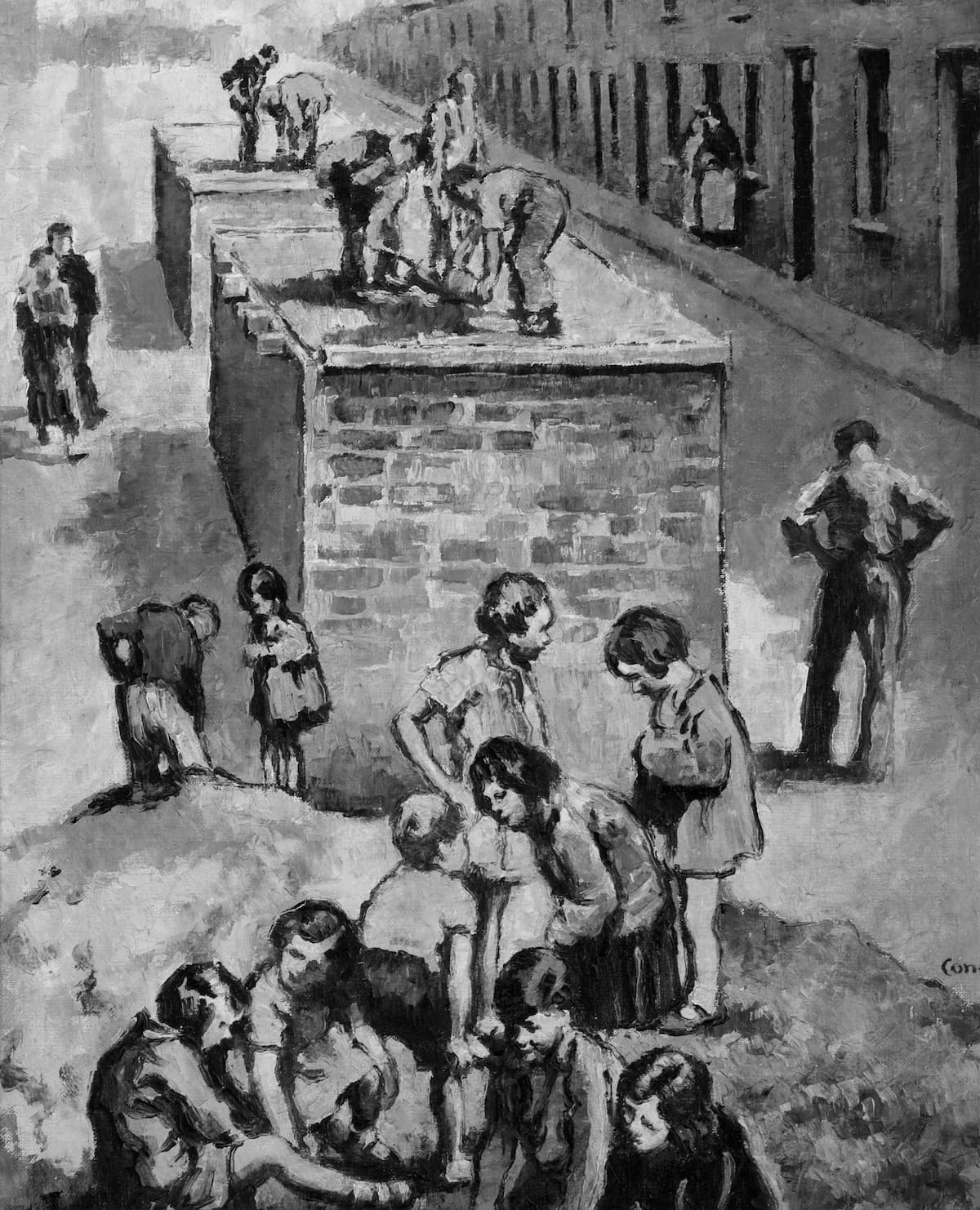

BELUM.U261,Building an Air-Raid Shelter (c.1940-41), William Conor, 1881-1968, © The Estate of William Conor, Ulster Museum Collection.

0:00

Read the story

Inspired by the rich collections of National Museums Northern Ireland and the Northern Ireland War Memorial Museum, celebrated author Glenn Patterson weaves together different personal experiences of the bombing of Belfast in April 1941. In ‘The sound that will never leave you’ Patterson evokes the intense experience of watching Belfast being bombed from the relative safety of the surrounding hills as well as being right at the centre of the attack as bombs dropped by German aircraft explode all around...

This content was created during COVID-19

Between 10:40 pm on the night of the 15 April 1941, Easter Tuesday, and 5 am the next day, German bombers dropped 200 tonnes of explosives on the city of Belfast, damaging at least half the houses in the city and killing more than 700 people: outside of London, it was one of the worst death tolls in a single night in the entire Blitz.

Belfast did not have anything like enough shelters for a city of almost half a million people. Those who could, fled to the hills that ring the city. Those who couldn’t, did their best to protect themselves with whatever was to hand.

Voice 1, Male:

The sound that will never leave you is horses, their hooves as they run in circles on the hard ground of the sloping field where you sit with your sisters and brothers, on the bench seat your father lifted out of the family car when the [air raid] sirens went and carried across his shoulder all the way up the Ligoniel Road and into the hills, giving you the best view of the light show that is the mass bombing of your city – oh, look, you say, and that was a big one, and where was that one do you think? – and pity the ones that didn’t get out, your mother says…

Voice 2, Female:

The sound that will never leave you is the sound of your best friend’s heart, a half-beat after your own, her breath as it tries – quick, quick, quick – to keep up and crosses over with yours coming back then off the sides of the galvanized tin bath, which in a moment of inspiration and improvisation you have put over your heads as you stand – moment of inspiration number two– with your backs against the wall separating the yard from the entry, and the whistle beyond – oh, Janey, oh, Janey, oh, Janey – of the bombs… Which have not let up now for hours it feels like.

Voice 1, Male:

You wonder what there is down there left to bomb. Whatever it is they seem to be trying very hard to find it – over here maybe, or over here, or over here, or over here.

Voice 2, Female:

Her heart, your heart, the whistles, closer, closer, closer…

The tin bath clattering in the yard as you bolt through the door of the working kitchen and into the hole under the stairs emptied long since of its coal

Oh, Janey, oh, Janey, oh, Janey

Voices 1 and 2 alternating:

And then

at last

the all-clear sounds

and for a moment

afterwards

nothing

Voice 1, Male:

And then there is another sound, like a football crowd, you think, jeering a bad decision

Voice 2, Female:

Or in some of the picture houses when they play the anthem

Voice 1, Male:

But it’s not that –

Voice 2, Female:

or that –

Voice 1, Male:

at all.

Voice 2, Female:

It is the sound of the living hit by the dawning fact of the dead

Voice 1, Male:

You get up off the car seat. Come on then, your father says, we’ll see what’s what.

Voice 2, Female:

You step out of the no-coal hole, out of the working kitchen door. The yard wall is gone. The tin bath’s flat as a tin lid. It will be a while before the keening dies.

It will be a while before your breathing returns to normal.

Voice 1, Male:

It will be a while before the horses’ heads tell their hooves that it’s all right

They can stop running now.

They can stop running

They can stop.